Tundra Swans

Tundra Swans are North America’s most abundant swan species. They were formerly called the Whistling Swan. The Whistling Swan and the European counterpart, the Bewick’s Swan, were combined into one species now known as the Tundra Swan. The only difference between the two is where they nest and winter and the Bewick’s form has a lot of yellow on the bill

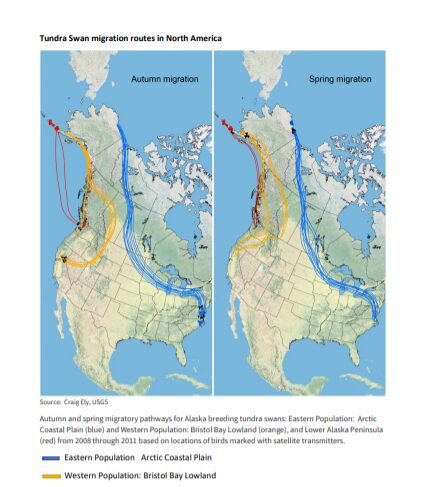

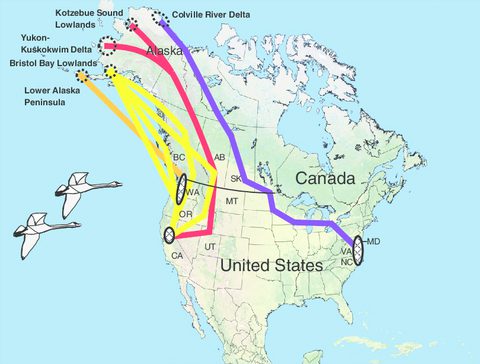

North American Tundra Swan management is divided into two populations based on where the swans winter: Eastern Population and Western Population. Swan surveys in 2015 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimate about 117,100 Tundra Swans in the eastern population and about 56,300 in the western population.

Survey data shows that some WP Tundra swans winter in coastal areas from Southeast Alaska to San Francisco Bay. In northern areas, WP swans usually winter with the Pacific Coast Population of Trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator). About 300–500 swans winter along the southern British Columbia coast with most of the Pacific Coast Trumpeter swans. Other notable wintering areas include about 5,000 swans in Washington, mostly in the Skagit River Delta; up to 10,000 swans in Oregon along the Columbia River from the Columbia Basin to the mouth and in the southwestern part of the state; and about 5,000 swans in Utah on the Great Salt Lake.

Washington’s Tundra Swans are part of the Western Population. Tundra’s both migrate through and winter in various areas throughout the state both on the east and west side of the Cascade mountains. These swans do have a strong fidelity between specific breeding grounds and wintering areas in Washington.

Management Plan: Western Population of Tundra Swans

Click below to download

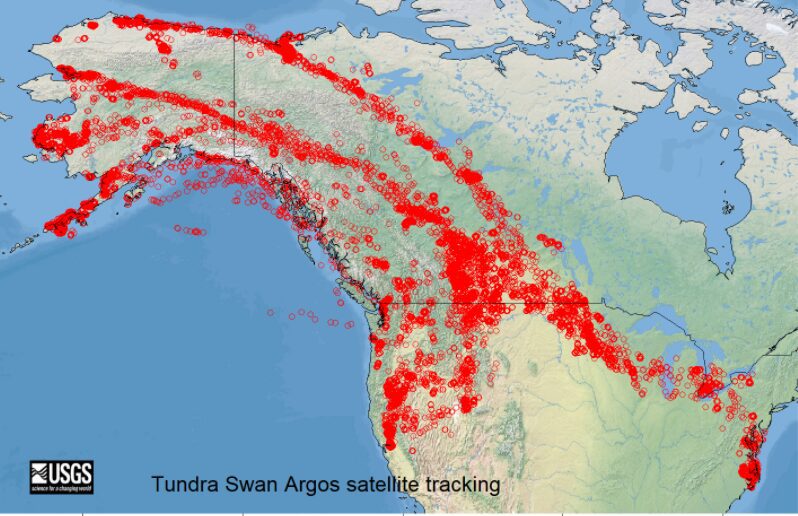

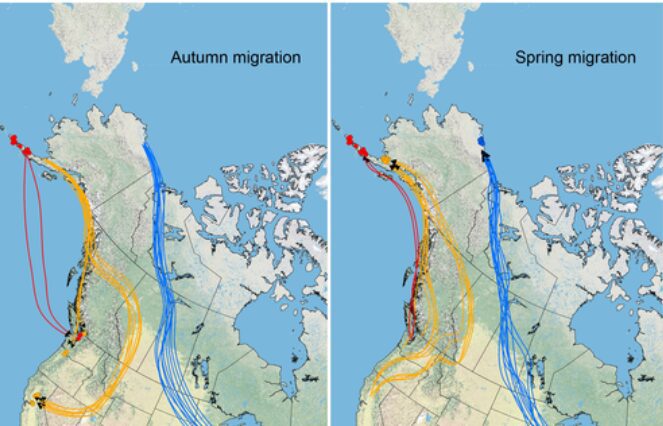

Tundra Swan Migration Routes

Click below to download

More About Tundra Swans

Habitat

Tundra Swans that winter and migrate through Washington State nest in the wet coastal Arctic tundra of Alaska. During migration and through the winter, they inhabit shallow lakes, slow-moving rivers, agricultural fields, and coastal estuaries. When Trumpeter Swans first reappeared in Washington, there was a habitat separation between the two swans, with the Trumpeters on fresh water and Tundras on salt water. This separation is no longer seen, and mixed flocks are common in the agricultural areas of western Washington.

Diet

Historically Tundra Swans ate invertebrates and submerged, aquatic vegetation. While some Tundra Swans still use this food resource, it has severely declined at migratory stopover and wintering areas. This has led the swans to shift to an agricultural winter diet. This behavior began in the 1960’s along the Washington to California coastal zone. The diet of mostly grains and cultivated tubers, especially potatoes, left in agricultural fields through the winter. There is a strong correlation between dairy farms that grow field corn for their cows and winter use of these harvested fields by swans in Washington.

Migration Status

Tundra Swans migrate long distances and family groups will stay together both in migration and on the wintering grounds the first year. They leave the nesting area in early fall, usually in late September or early October to stage in nearby estuaries before heading to the wintering grounds by mid-fall. In the spring, the birds make shorter flights with more stopovers for feeding so they can arrive on the breeding grounds in good condition.

Behavior

During the breeding season, Tundra Swans forage mostly on the water, using their long necks to reach as much as three feet below the water's surface. During migration and in winter, much of their feeding is on land in fields. A long-lived species, they form long-term pair bonds.

Nesting

Nests are located near a lake or other open water, in an area with good visibility. Both parents help build the nest, which is a large, low mound of plant material with a depression in the center. The pair may reuse the nest from year to year. The female incubates the 4 to 5 eggs for about a month, with the male assisting. After the eggs hatch, both parents tend the young, leading them to sources of food where the young feed themselves. Tundra swans can fly at 90 days of age. This is 12-14 days earlier than when Trumpeter Swans take first flight. There are fewer ice free days in the higher latitudes, thus Tundra Swans can take advantage of nesting further north.